Voices Of Color: Bayard Rustin, the Invisible Soldier for Civil Rights

“We need in every community a group of angelic troublemakers."

-Bayard Rustin.

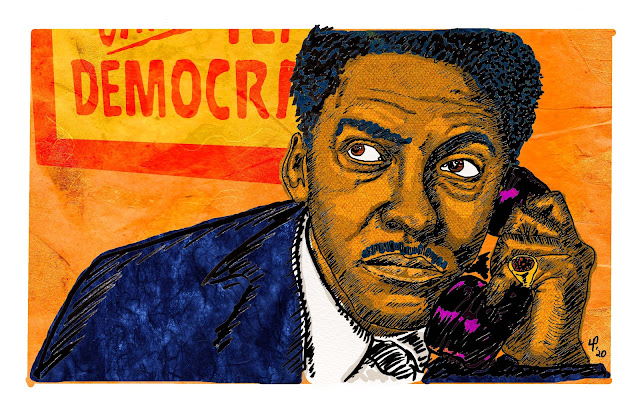

Hello, friends, and welcome back to the blog. I know Pride month is over and we have moved on into the fits of an extra hot Summer. However, I had completed this illustration of Bayar Rustin some time ago and wanted to write and post the accompanying blog post for it and him. So, here we go...

Bayard Rustin is probably the most well-known unknown leader in social movements for civil rights, socialism, nonviolence, and gay rights. He was one of Dr. Martin Luther King's closest mentors and valued advisors. He spent his entire life fighting for the rights of others, sometimes at the expense of fighting for the acceptance of himself. I call him the invisible soldier because he spent so many years behind the scenes on key civil rights political events because he chose to be open about his sexuality. Calling him a soldier is meant in irony as he was a conscientious objector to war. However, as a pacifist, he still fought with as much fervor and conviction as a soldier would on a war's battlefield, and his political activism was anything but passive. Today we look at and honor his life, his accomplishments, and his legacy.

Rustin was born in West Chester, Pennsylvania in 1912. He was nine of twelve children. He was sent to live with his maternal grandparents due to the young age of his parents. Most of his childhood he believed that his grandmother was his mother and his mother was his sister. He grew up in the large home his grandparents lived in. His grandmother was a Quaker and an active member of the NAACP. Rustin was first exposed to the Quaker values he would later adopt and live by in his adult life in this very home. He was also exposed to some very influential political figures. NAACP leaders, such as W.E.B. Du Bois and James Weldon Johnson were frequent guests in his home. These visits inspired Bayard to begin to get involved in political protests. At a young age, he helped campaign against racially discriminatory Jim Crow laws.

In 1932, Rustin attended Wilberforce College and was very involved with many on-campus groups including the Omega Psi Phi fraternity. However, he was promptly expelled from the school after organizing a strike. After completing an activist training program in 1937, Rustin moved to Harlem where he continued to study at the City College of New York. Again, Rustin became very involved in fighting against the injustices he saw. He was part of the efforts to defend and free the Scottsboro Boys, nine young black men in Alabama who were accused of raping two white women.

Something that many people may not know about Bayard Rustin is that, outside of his very active political life, he was an accomplished tenor vocalist. He obtained music scholarships for it both from Wilberforce College and Cheyney State Teachers College. In 1939, Rustin was in the chorus of the short-lived Broadway musical, John Henry. This is where he met blues singer, Josh White, who later invited Rustin to join his gospel and vocal harmony group, Josh White and the Carolinians. They made several recordings together. Rustin became a regular performer at the Cafe Society nightclub in Greenwich Village. This widened both his social and intellectual contacts in the city. A few albums on Fellowship Records featuring his singing, such as Bayard Rustin Sings a Program of Spirituals, were produced from the 1950s through the 1970s.

In his early politics, Rustin became involved with the local communist, socialist, and Quaker groups. He was a key figure in the formation of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE.) He also worked as a race relations secretary for the Fellowship of Reconciliation. This connected him to other socialist figures that would play key roles in Rustin's political life; particularly A. Phillip Randolph. In 1942, Rustin staged a spontaneous protest while riding a bus in the South. He refused to sit in the rear and sat in a second-row seat until he was arrested by police shortly after that.

Rustin speaks to the incident, "As I was going by the second seat to go to the rear, a white child reached out for the red necktie I was wearing and pulled it. Whereupon its mother said, 'Don’t touch a nigger.' Something happened, and I said to myself, If I go and sit quietly in the back of that bus now, that child who was so innocent of race relations that it was going to play with me, will have seen so many Blacks go in the back and sit down quietly that it’s going to end up saying, 'They like it back there, I’ve never seen anybody protest against it.' That’s what people in the South would say.

So I said, I owe it to that child, not only to my own dignity, but I owe it to that child that it should be educated to know that Blacks do not want to sit in the back, and therefore I should get arrested letting all these white people in the bus know that I do not accept that."

During World War 2, Rustin was imprisoned as a conscientious objector from 44-46. This did not stop him from fighting for the rights of others as he continued to organize with the other inmates to stage protests right within the prison walls. In 1948, he traveled to India to learn the techniques of nonviolent civil resistance directly from the leaders of the Gandhian movement. This study would become not only important in influencing Bayard's life but also the lives of other influential people.

Bayard first knew, to himself, that he was gay when he was in high school. He was a very popular and successful athlete. He was on the championship football team and champion track team. He won the all-state high school championship for tennis. all the boys in the school liked him and they made him manager so that he could get his four letters. " I knew then that my affection was far more for men than women. When I look back upon it I also understood that my experience there had been a very liberating one. And because of what I had to put up with there, I also was preparing myself with putting up with what I had to do as a gay person." says Rustin of his high school days.

He confided in his grandmother that he preferred to spend time with males rather than females. She responded, "I suppose that's what you need to do." While she knew about his sexuality after that conversation, she did not speak openly about the matter. However, she did one caution Rustin after he had been spending so much time with a particular young man. She told him to be very careful associating with him as he (Bayard) was the type of person who can easily get into trouble where young men were concerned. She told him to always associate with people "who have as much to lose as you have."

Bayard did not openly declare his homosexuality until he was arrested on that bus in 1942. Rustin speaks about his coming out, "Now, it occurred to me shortly after that that it was an absolute necessity for me to declare homosexuality because if I didn’t I was a part of the prejudice. I was aiding and abetting… The prejudice that was a part of the effort to destroy me. And that in the long run the only way I could be a free whole person was to face the shit. But from my own experience, I know how long it can take till you free yourself. Thirty-four years is a long time to free yourself."

Rustin was arrested in Pasadena, California, in January 1953 for sexual activity in a parked car with two men in their 20s. Originally charged with vagrancy and lewd conduct, he pleaded guilty to a single, lesser charge of "sex perversion" and served 60 days in jail. The Pasadena arrest was the first time that Rustin's homosexuality had come to public attention. He had been and remained candid in private about his sexuality, although homosexual activity was still criminalized throughout the United States. This resulted in him leaving the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR.)

Bayard later met and became romantically involved with Walter Naegle. They moved in together and began to work together as well. Naegle became Rustin's right hand. Due to the lack of marriage equality at the time, Rustin and Naegle took the then-not-unusual step to solidify their partnership and protect their union legally through adoption: in 1982 Rustin adopted Naegle, 30 years old at the time.

"Without him (Walter) I’m hopeless."

-Bayard, of his life partner (Washington Blade interview with Peg Byron, 1986)

Bayard played a key role in the civil rights movement for African Americans. He helped organize the Journey of Reconciliation in 1947. These were the first "Freedom Rides" to test the 1946 ruling of the Supreme Court that banned racial discrimination in interstate travel as unconstitutional. Groups of men were organized to ride in pairs all throughout the South. Many were arrested. Rustin, himself, served a month on a chain gang in North Carolina for violating the state's Jim Crow laws regarding segregated seating. These charges were posthumously dismissed in 2022.

Rustin was a valued and trusted advisor and mentor to Dr. Martin Luther King. In 1956, Bayard began to advise Dr. Martin Luther King on the tactics of Gandhian nonviolent resistance. "I think it's fair to say that Dr. King's view of non-violent tactics was almost non-existent when the boycott began. In other words, Dr. King was permitting himself and his children and his home to be protected by guns." Bayard eventually convinced Dr. King to abandon the armed defense. Bayard taught and advised Dr. King on the methods and techniques of non-violent resistance that he had studied during his time in India. One of the first influences Rustin had on Dr. King was during the Montgomery bus boycott. He helped Dr. King shape and form the boycott in a more peaceful, non-violent, and ultimately more successful way.

A year later, they would both form the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. However, again, Rustin's sexuality would play a part in his eventual removal from the organization. While organizing a civil rights march in southern California at the 1960 Democratic National Convention, Rustin and Dr. King were met with a backlash orchestrated by US Representative Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. Powell, in hopes to avoid the march, threatened to sensationalize a rumor that Rustin and Dr. King were involved together in a homosexual affair. This resulted in Dr. King's cancelation of the march (against Rustin's fervent advisement not to.) And with pressure from the leadership of the SCLC, Dr. King was advised to ask Rustin to leave the organization citing that his open sexuality would be a threat to the organization's future efforts. Rustin stepped down and left the organization.

In 1962, Rustin became involved in the March on Washington. He was recruited by A. Phillip Randolph who personally pushed Rustin forward as the best and logical choice to organize it. Rustin was instrumental in organizing the march. He drilled off-duty police officers as marshals, and bus captains to direct traffic, and scheduled the podium speakers. NAACP chairman, Roy Wilkins, felt differently. "This march is of such importance that we must not put a person of his liabilities at the head." Rustin once again stepped down from the spotlight due to his sexuality and became Randolph's deputy, while Randolph served as march director. Rustin feared his legal issues would pose a threat to the march. Despite this, Rustin did become well known for his involvement with the march, and he appeared with Randolph in a photograph on the cover of LIFE magazine in 1963.

"I just wish that he had shown the strength in ’62 that he showed when he backed me completely in ’63. But he was a year older, and had another year’s experience."

-Bayard of King (Washington Blade interview with Peg Byron, 1986)

Bayard Rustin had so many other political contributions. He was a silent contributor to the essay "Speak Truth to Power." He believed that his sexuality would compromise the political validity and success of the document. While there in India in 1948, he formed the American Committee on Africa to support the historic Defiance Campaign in South Africa. Its later mission and purpose was to work to change U.S.–Africa relations, and to promote political, economic, and social justice in nations of Africa. Essentially everywhere that Bayard went where he saw injustice, he rallied people together and created action to help fight against those injustices. He became an instrumental organizer in the 1964 New York City school boycott to desegregate NYC public schools. He was an advisor to the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.

Bayard wrote the influential article From Protest to Politics that aimed to more closely unify the Democratic Party to the Civil Rights Movement. Rustin argued that since black people could now legally sit in the restaurant after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, they needed to be able to afford service financially. He believed that a coalition of progressive forces to move the Democratic Party forward was needed to change the economic structure. He also argued that the African American community was threatened by the appeal of identity politics, particularly the rise of "Black power". He thought this position was a fantasy of middle-class black people that repeated the political and moral errors of previous black nationalists while alienating the white allies needed by the African American community.

Rustin increasingly also worked to strengthen the labor movement, which he saw as the champion of empowerment for the African American community and for economic justice for all Americans. He contributed to the labor movement's two sides, economic and political, through the support of labor unions and social-democratic politics. In 1966 he chaired the historic Ad hoc Commission on Rights of Soviet Jews organized by the Conference on the Status of Soviet Jews, leading a panel of six jurors in the commission's public tribunal on Jewish life in the Soviet Union. The plight of Jews in the Soviet Union reminded Rustin of the struggles that blacks faced in the United States.

"Today, blacks are no longer the litmus paper or the barometer of social change. Blacks are in every segment of society and there are laws that help to protect them from racial discrimination. The new "niggers" are gays... It is in this sense that gay people are the new barometer for social change... The question of social change should be framed with the most vulnerable group in mind: gay people."

-Bayard Rustin (The New Niggers Are Gays speech)

Rustin had some very strong thoughts and stands on gay rights, which he did not engage in until the 1980s. He was urged to do so by his partner Walter Naegle. Rustin testified in favor of the New York City Gay Rights Bill. In 1986, he gave a speech "The New Niggers Are Gays." Also in 1986, Rustin was invited to contribute to the book In the Life: A Black Gay Anthology. He elaborates that you can't just fight for white gay rights, and exclude the needs and democratic rights of gay people of color. The only way for any of it to succeed is to stand all together and fight for gay rights, period.

Rustin was not involved in the struggle for gay rights in his youth. Even though he came "out of the closet," and had no problem with being publicly identified as homosexual, he felt that it would be dishonest to present himself as one of the activists at the forefront of the struggle for gay rights. He wasn't. He contributed to the fight later in his life, but it did not equate to the same fervor and weight for which he had served in other civil rights activism. He, in fact, considered sexual orientation to be a private matter, despite being openly gay. As such, he felt that his sexual orientation has not been a prime factor that has greatly influenced his role as an activist.

"My general thesis was that the human condition is of a single pattern. And that none of us is free and none of us can practice democracy fully so long as any other segment of the community or any country is not democratic. And that, therefore, it is very important that as gay people sought their rights, that they understand the interconnection and that therefore their working for the rights of all other groups was in their own selfish, as well as in their own humanitarian, interests."

-Bayard Rustin (Washington Blade interview with Peg Byron, 1986)

Rustin died on August 24, 1987, of a perforated appendix. An obituary in The New York Times reported, "Looking back at his career, Mr. Rustin, a Quaker, once wrote: 'The principal factors which influenced my life are 1) nonviolent tactics; 2) constitutional means; 3) democratic procedures; 4) respect for human personality; 5) a belief that all people are one."

He has left a vast legacy in his wake that is anything but invisible. Many of the committees and coalitions he either helped to form or formed on his own, are still going strong with the same fervor and convictions that Rustin has when forming them. Several buildings have been named in honor of Rustin, including the Bayard Rustin Educational Complex located in Chelsea, Manhattan; Bayard Rustin High School in his hometown of West Chester, Pennsylvania; Bayard Rustin Library at the Affirmations Gay/Lesbian Community Center in Ferndale, Michigan; the Bayard Rustin Social Justice Center in Conway, Arkansas, and the Bayard Rustin Center for Social Justice in Princeton, New Jersey. Rustin is one of two men who have both participated in the Penn Relays and had a school, West Chester Rustin High School, named in his honor that participates in the relays. In 1985, Haverford College awarded Rustin an honorary doctorate in law. He has inspired two films made about him: Brother Outsider and Out of the Past. In 2011, the Bayard Rustin Center for LGBTQA Activism, Awareness, and Reconciliation was announced at Guilford College, a Quaker school. In 2012, Rustin was inducted into the Legacy Walk, an outdoor public display that celebrates LGBTQ history and people. In 2013, Rustin was selected as an honoree in the United States Department of Labor Hall of Honor.

On August 8, 2013, President Barack Obama posthumously awarded Rustin the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award in the United States. Walter Naegle, Rustin's life partner, accepted the award on Rustin's behalf. In an interview with the Making Gay History podcast, Walter Naegle (Bayard's life partner) speaks about accepting this prestigious award. "It was not a place where I ever imagined that I would be myself. This was about Bayard. Before we went in for the ceremony, there was kind of like this receiving, sort of like a receiving line. President Obama and Mrs. Obama came through and, you know, they talked to me and they said, you know, Bayard was somebody who really influenced, influenced them, their politics, their ideas, their activism. And so they were happy that he was… to be the ones that were giving this award. At the beginning of the ceremony, he made remarks about all of the recipients, and he said things about Bayard of course, and he ended—I’m paraphrasing here although I should know it by now because I’ve heard it so many times—he ended by saying something like, you know… He ended by saying something like, 'No medal can undo that or replace that,' and he was talking about the treatment that Bayard had received."

What else can be said about Bayard Rustin? He lived a life of such struggle and fight so that others would not have to fight so hard. It's almost criminal in a way for his contributions to so many civil rights causes to be muted and pushed into the background because he was an openly gay man. Even though it is nice to see that he is finally being openly recognized after his death, He never received the credit he was due in his lifetime, and that is a shame. I leave you all with some powerful words spoken and sung by the man, himself.

keep making art.

Cheers,

LEWIS

***Biographical information and interview quotes are sourced from Wikipedia

and the Making Gay History Podcast.

Comments

Post a Comment