ROCKING THE ART: VOL.2: MAKE THE DIFFERENCE

Welcome back, friends, and welcome back to Rocking the Art: Vol.2. We are going to discuss an album art project that not only was a challenge to understand conceptually but also quite a puzzle to piece together, literally. But, before we get into that, I wanted to review a brief little survey into the history of album art and design.

An album cover or "album art" is the front packaging art of a commercially released studio album or other audio recordings. The term can refer to either the printed paperboard covers typically used to package sets of 10- and 12-inch 78-rpm records, single and sets of 12 in LPs, sets of 45 rpm records (either in several connected sleeves or a box), or the front-facing panel of a cassette J-card or CD jewel case packaging, and, increasingly, the primary image accompanying a digital download of the album(or of its tracks.)

Photo credit unknown.

Album art has also been discussed as an important postwar cultural expression. They have gone together like "Ramma Lamma Lamma Da Diggity..." or like Peanut Butter and Jelly. Most of the time, when we think about our favorite albums (or even music singles [when those were a thing]) we almost ALWAYS picture the album cover art in our minds. They are pretty much synonymous even in this age of digital music when many people aren't buying physical copies of the albums they love. However, there was a time before art was the Ying to Music Recoding's Yang. Recorded music formats used to be stored in very plain and not so artistic ways.

Around 1910, 78-rpm records replaced the phonograph cylinder as the medium for recorded sound. The 78-rpm records were issued in both 10- and 12-inch diameter sizes and were usually sold separately, in brown paper or cardboard sleeves. The sleeves were sometimes plain and sometimes printed to show the producer or the retailer's name. These were invariably made out of acid paper, limiting archival longevity. Generally, the sleeves had a circular cutout allowing the record label to be seen. Records could be laid on a shelf horizontally or stood upright on an edge, but because of their fragility, many broke in storage.

Let's talk about the "Album" part of "album art." The name “album” comes from the pre-war era. It literally referred to the album that contained the 78rpm shellac disc. Beginning in the 1920s, bound collections of empty sleeves with a plain paperboard or leather cover were sold as "record albums" (similar to a photograph album) that customers could use to store their records. These empty albums were sold in both 10- and 12-inch sizes. The covers of these bound books were wider and taller than the records inside, allowing the record album to be placed on a shelf upright, like a book, and suspending the fragile records above the shelf, protecting them.

German record company Odeon pioneered the "album" in 1909 when it released the Nutcracker Suite by Tchaikovsky on four double-sided discs in a specially designed package. (It is not indicated what the specially designed package was.) The practice of issuing albums does not seem to have been taken up by other record companies for many years.

The real change in album art and design came in the 1930s. The illustrated covers by Alex Steinweiss (for singers such as Paul Robeson, or the classical records of Beethoven) led to huge increases in sales. However, it was the advent of the long-playing 33⅓rpm record that changed everything. The heavy paper used for 78s damaged the delicate grooves on LPs, and record companies started using a folded-over board format sleeve. The format was ripe for artistic experimentation and interpretation.

A landmark artwork that first attracted mass attention in America was the Capitol Records design for Nat King Cole’s The King Cole Trio album – a lively abstract image featuring a double-bass, a guitar, and a piano keyboard under a gold crown. The four 78rpm records housed inside made history, topping the first Billboard Best Selling Popular Record Albums chart, on 24 March 1945. There was no turning back.

Many of the greatest covers of all time are associated with the post-war jazz and bebop era. Jim Flora’s distinctive drawing style was a light-hearted blend of caricature and surrealism, with humorous juxtapositions of physically exaggerated characters, some with Picasso-skewed eyes. His celebrated portrayals included Louis Armstrong and Shorty Rogers.

It wasn’t only designers who played a part in this era; photographers became a key component of the process. One of the most renowned photographers was Charles Stewart, responsible for cover shots on more than 2,000 albums, including his wonderful portraits of Armstrong, Count Basie, John Coltrane, and Miles Davis. When speaking of another famed cover photographer (Herman Leonard) Quincy Jones remarked that “when people think of jazz, their mental picture is likely one of Herman’s.”

Sometimes it was just bold use of typography – as in Reid Miles’s design for Jackie McLean’s It’s Time – that produced a simple yet eye-catching triumph. Miles said that in the 50s typography was in a renaissance period. Sometimes companies chose an iconic symbol or look that would define their output.

1956 was the year that a landmark photograph was taken of Ella And Louis. The pair were so famous by then that they did not even have their names on the album cover, just the gorgeous image taken by Vogue photographer Phil Stern, known for his iconic studies of Marlon Brando, James Dean, and Marilyn Monroe. The image-cementing photograph of rock stars would later play a major part in some of the great 60s and 70s album covers.

In the 60s it became fashionable for bands to commission covers from artists and art school friends. The Beatles famously worked with Peter Blake and Richard Hamilton; The Rolling Stones with Warhol and Robert Frank. During this time there was SO MUCH creative innovation in experimenting with the art of the album cover, but nothing quite matched the impact of the Blake/Jann Howarth cover for Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. That cover truly broke the mold, not least for being an album where music and visuals began to meld as one creative entity.

Album art as a concept was the new thing, and British designers Storm Thorgerson and Aubrey Powell were at the forefront with the firm Hipgnosis. Some of their designs have become symbols of music in the 20th Century, such as the giant inflatable pig over London’s Battersea Power Station which graced the cover for Pink Floyd’s Animals (1977); or the disturbing image of blonde-haired, nude children climbing the Giant’s Causeway for Led Zeppelin’s Houses Of The Holy (1973). Thorgerson said they wanted to encapsulate in art what bands were trying to say in their music: “Pictures of a band, what do they tell you? They tell you what they look like, but nothing about what’s in their hearts, or in their music,” he said. “If you were trying to present an emotion, or a feeling, or an idea, or a theme, or an obsession, or a perversion, or a preoccupation, when would it have four guys in it?”

The 60s through the 70s, 80s, 90s, and into the 21st century saw new avenues for marketing and revenue for bands and solo musicians that weren't previously seen before. Logos, t-shirts, lunchboxes, coolers, posters... merch. It was an ever-expanding frontier that further bonded this relationship between music, art, and pop culture. Bands were no longer just great bands, they were successful brands!

This is just a small sliver of the vast history between art and music. It's just a small sliver of the history of album art specifically, but we must press on with other things. I'll go more into specific artists and designers in the next volume of this little blog mini-series.

Let's talk about Rob...

The album art and packaging design for Rob Bailey's the Difference album was a particularly challenging but fun project to work on. This is Rob's first recorded album and in our initial project discussions, he advised that the collection of songs was sort of a hodgepodge of songs he had written throughout his life spent in music.

He gave me a collection of photographs that dated from the present back to 20 years previous. There really wasn't any cohesive theme or concept connecting them all other than they were songs he wrote over time. While the music is good and I liked the songs after listening to the album a few times. I realized that, conceptually, the art and design for the record could not and would not be able to come from the content of the songs themselves. I had to come up with other ideas of how I could visually represent this collection of music. After some creative thinking, I began to think of making time the cohesive theme, quite literally.

I wanted to use a "time Line" as the visual theme for the album art, but not a single line we would normally think about that might augment a graph or chart within a history book. My timeline will pull from 2 different sources of Inspiration: Conceptually it is "loosely" based (pun intended) on String Theory. In execution, it is based on the aesthetics of continuous line drawing.

****A quick aside: Unfortunately due to technical difficulties after the project's completion, there are little to no process images for me to show you. (And by technical difficulties, I mean the computer I created this project on died and, like a dingbat, I did not have it backed up or copied anywhere. Mercury was definitely in retrograde, I'm sure of it.) I will be pulling examples of visuals to help me explain my process for this project from other sources.****

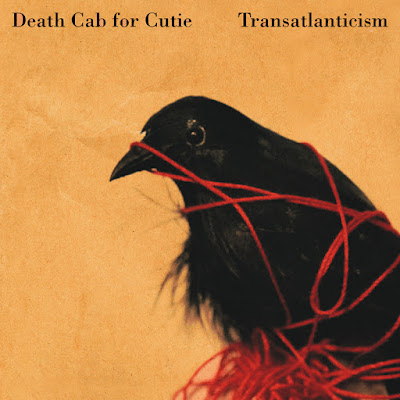

String theory (in the simplest terms) states that everything in our Universe is made up of tiny vibrating strings. These strings are one-dimensional objects and are identical to one another. Every fundamental particle that we know such as electrons, quarks, photons, gluons, etc are made up of these strings. The reason why one particle appears to be different than another particle is that both vibrate at different frequencies. These strings are very tiny. Though, when I think of them, I think of the red string used in the album art for Death Cab For Cutie's Transatlanticism (pictured at the end of this blog.) If you've ever seen the film I Heart Huckabees, the philosophy of how the universe is connected is quite similar. "Everything is the same, even if it's different." -Albert Markovski

For those who are not familiar with the term, a continuous line drawing is exactly what it sounds like it is. Continuous line drawings are also known as Contour Drawings. The name is derived from the process of drawing which involves following the contours or outline of a subject without lifting the pencil off the paper until the drawing is complete.

If this wasn't a challenge enough, I wanted to create the illusion that no matter how you were holding the album, either opened or closed, whether one single flap of liner notes opened or the entire foldout opened, the continuous line connected from where it ran off the page of where you were looking, to literally wrap around to the opposite side if you flipped over what you were looking at. Hitting on the nose that "Everything is connected."

I met with Rob and pitched him this idea. He absolutely loved it, which made me both happy and nervous. I'm always excited when a client loves what I come up with, but did I bite off more than I could chew with this one? I began to get nervous, because, now I had to deliver on this very complicated concept and I had ABSOLUTELY NO IDEA how I was going to accomplish it. lol. This might have been a challenge that would break many other people's brains, but I was determined to achieve this goal. I like to solve puzzles and I usually stick with them until I do.

It took me roughly 2.5 weeks of trying different ways and methods to solve this tricky puzzle. I measured and cut out "to size" physical elements of the cd packaging out of plain drawing paper. I then would make my measurements and using my pencil work on solving EXACTLY where each "fold-over" point needed to be to create this ambitious illusion. It involved a lot of paper crumpling, garbage basketball ringing, under-breath mumbling, and ALOT of floor-pacing. I probably lost some hair over it, I'm sure. lol.

In the end, I did achieve my goal in creating this multiple wrap-around illusion to further the visual concept of a single life and all its many twists and turns along its journey. The puzzle was, of course, solved in pencil and paper first. Now I needed to create a more "developed" version of what I had drawn. The plan was to take my "thread" and glue it down over the lightly redrawn continuous line drawings (simulating the wire sculptures I was inspired by. I wish I had taken photos of them.)

If this wasn't enough to drive you, the reader, mad with imagining doing this yourself, Imagine doing it 3 times over. (wide eye emoji) Because of the nature of the materials, I chose to use, I had to redo this part of the project 3 times. Yes, 3 times, and it's my fault, honestly. My first choice in "thread" material was actual guitar string. I wanted to keep the aesthetic as close to the concept as possible. This conclusion only seemed natural. However, I had never worked with guitar string as an art material before and it is not very inclined to hold a sculpted shape; even when glued down to a surface. It was maddening and heartbreaking to scrap this material.

My second attempt was taken from my previous experience with sculpting those continuous line drawings. I began working with the soft copper-colored wire and it was yielding better results. I ran into problems when I needed the wire to bend in much narrower and tighter ways. Due to the nature of how this project was going to be assembled, I had to sculpt the "thread" exactly to size, so that when scanned, it fit perfectly with the other puzzle pieces. This material, in the end, also was not the right choice.

In my third and successful attempt at this part of the project, I utilized a copper-colored embroidery thread. It completely yielded to all the forms it needed for. However, there was also a snag in some of the more tightly, smaller drawn detailed images. I thought sideways and came up with a creative solution to include some actual continuous line drawings within the design as well as the thread sculpted visuals. I thought this created a more tactile bridge between the photographs, digital typography, and the threaded timeline. The third time's the charm and the embroidery thread did the trick.

After this, I scanned all the puzzle pieces into my digital art studio for assembly. I was very pleased to report that all that careful planning and meticulous measuring paid off. EVERYTHING fell into place perfectly and the rest of the project came off without a hitch. I digitally removed my "working" background from the thread image scans and superimposed them over a handmade colored/textured paper. It's one of my favorite handmade papers I've come across (I collect a variety of papers to use for my art/illustration/design projects.) This one, in particular, has a beautiful shade of blue which complimented the copper-colored thread so well and gave an abstract impression of a globe with water and land masses or an impression of Outerspace. I like either interpretation.

The white continuous line drawings are also super-imposed digitally onto the paper to give the illusion that they are drawn onto it. The thread appears to "hover" just above the surface of the paper. This was an intentional design choice as I wanted to create the physical illusion that this thread had a "life" of its own and was moving across this colored/textured surface.

The last "leg" of this tour is the typography. I remember giving Rob a few choices on the cover art itself. The rest of the type choices were chosen based on his final decision. The only thing that he and I did not agree on in this project was the inclusion of all of the song lyrics. Originally, I had pitched the idea of printing only an excerpt from each song so that it could be featured more. I thought we could create an accompanying website/blog that featured all the song lyrics in their entirety. Rob did not like this idea and was insistent on including all of the song lyrics within the fold-out. I felt this diminished their prominence, but Rob was very happy with the result. At the end of the day, in this collaborative medium that is all that counts and matters: a happy client.

Overall, I'm very happy with the outcome of this album cover and packaging design. Though challenging, the concept was cool and the 3-d illustrating was fun. I'm honored to be a hallmark in Rob's ever-evolving career and musical timeline. I wish him the best of luck in his future career.

Thanks, once again, friends for stopping by to listen to me talk about my art. In closing, I wanted to share just a handful of some of my favorite album covers in no particular order or ranking. What are some of your favorite iconic album covers that helped shape your own musical world? I'd love to know. Share them in the comments below.

1.) Boys For Pele by Tori Amos

Atlantic Records. Photography by Cindy Palmano. Design by Paddy Cramsie.

2.) Melancholy and the Infinite Sadness by The Smashing Pumpkins

Virgin Records. Illustrations by John Craig. Design & Art Direction by Billy Corgan

Warner Bros. Records. Photography by Herbert Worthington.

Hand Lettering by Larry Vigon. Design by Desmond Strobel.

Barsuk Records. Paintings and Design by Adde Russell.

5.) Wildflowers by Tom Petty

Warner Bros. Records. Photography, Art Direction, and Design by Martyn Atkins.

I hope you all have a great week. Stay tuned for vol.3 coming soon. Until, next time, friends.

Keep dreaming, keep sketching, keep thinking, keep laughing, and most important of all, keep making art.

**Survey of Album Art History sourced from:

Cover Story: A History Of Album Artwork by Martin Chilton & Wikipedia

Comments

Post a Comment